It Wouldn't Be This Hard If I Was With The Right Person

By Lissa Carter, LCMHCS

My client had ‘come in hot’ (her words). She put her tea down forcefully on the table and leaned forward, her eyes expressive.

“Want to know why I’m late today? I was sitting out there in the car, in an argument, again, and to be honest I don’t even know what we were arguing about. If I were with the right person, it wouldn’t be like this—fights, misunderstandings, shutdowns, all the time. It shouldn’t be like this, right? Two fights before noon? It just really, really shouldn’t be this hard.”

I hesitated a moment and she started laughing. We’d been working together a long time, and she could read me pretty well. “What are you about to say?” she asked. “I’m not going to like it, am I?”

“Yeah, I think you’re not going to like it,” I said. “But I back what I am about to say with the full weight of my education and the confidence of years of counseling experience.”

“All right,” she said, sighing. “Sock it to me.”

I leaned forward.

“It depends.”

When I was training as a counselor, I was pretty sure my professors had a manual of how to correctly practice therapy that they were purposefully withholding because they thought the Socratic method would be a more effective teaching tool than just handing us the answers outright.

Now I find myself in the position of being the one who can’t for the life of me give a clear yes or no answer. The world of counseling, it turns out, is rife with maddening ambiguity. Because humans are complex. And the only thing more complex than a human is two humans trying to relate to each other.

“You’re right,” she said, settling back into the couch and crossing her arms. “I don’t like it. What a cop out.”

“Honestly, I would feel the same way if I were sitting where you are. But will you give a moment to redeem myself?”

As I said, this client knows me pretty well, and she knows all my tricks. She reached into the drawer where I keep my fidgets and pulled out my sand timer, which she dramatically flipped on the table between us.

“You have two minutes,” she said, and resumed her crossed-arm position.

Gauntlet accepted. I now present to you my two-minute condensed complexity-of-relationships spiel, as elicited by my wonderful, saucy, take-no-prisoners client.

Here goes.

Imagine that you could design the perfect little hermit house for yourself. It has everything you need to be wonderfully comfortable—your favorite books, games, foods, your favorite landscape surrounding you, access to all of the activities that bring you alive. You have everything you could possibly need or want.

Imagine yourself, now, after ten years of that life. I imagine you are pretty content. I imagine you have lived a relatively conflict-free life in which you could do all of the things (go to bed when you want, get up when you want, eat when and what you want, flow with your own rhythms and timing) that get logjammed when you have to navigate other people.

Now ask yourself: am I basically the same person I was ten years ago? Or have I grown?

When I do this little thought experiment, I have to admit to myself—dedicated introvert that I am—that I would not have grown much. I would have read A LOT and might be more knowledgeable on certain (predictable) topics. But I wouldn’t have grown. I would have been too comfortable to necessitate much growing. So—maybe—not all conflict is bad.

IMPORTANT CLARIFICATION: I am not in any way arguing that people who live alone aren’t constantly growing and changing. It’s not the alone part that causes the lack of growth. This thought experiment is about dwelling in a state of comfort and content, everything just as you like it, without any challenge. I have friends who live alone and are some of the most evolved people I know, because they’ve designed their lives to challenge them regularly.

Let me add as well that I am not arguing against the joys of long periods of contentment and calm! These are vital. As with everything else in counseling, it’s that maddening, maddening middle ground that we are going for. Enough safety and comfort to be well-cared for and rested, enough challenge to be activated and growing.

For example, we could do this the other way—if you are in a high-conflict relationship, you might imagine ten years alone and ten years with the person you are currently with—which version of you do you like better, ten years later?

The point I am trying to make is not that alone is bad and relationship is good. It’s that you can’t judge the ‘good’ness of a relationship by how easy it is. Not all conflict is bad. And all relationships, inevitably, contain conflict.

Most humans, when offered the chance to opt out of growth, will take that option every time. Change is hard and dangerous and we prefer homeostasis. So we tend, when left to our own devices, not to change. Even when we cognitively believe that we really value feedback, flexibility, and change--we’re up against our organismic design. Our default wiring is to prefer ease to challenge in most scenarios. But this doesn’t always lead to the best outcomes.

Enter: THE HUMAN RELATIONSHIP.

(To be fully transparent, the little sand timer had run out by now, but I was on a roll and my client kindly allowed me to continue speaking.)

Humans generate friction and drag on other humans. They like different music than you do and they put the wrong amount of spice in their food and they get up at categorically the worst time of day and they seem to deliberately misunderstand what you mean and they eat the last egg and put the empty egg carton back into the fridge.

And, as we balance our inner world with their inner worlds, as we learn to navigate our differences and our frictions by interacting with others, we will be challenged and changed. And it will often feel awful, because we would prefer the ease of homeostasis.

Now here’s the “it depends” part.

If, in the friction and drag of your relationship (and please be aware that I am not talking about the glorious, luminous limerence phase in which your brain chemistry medicates you to not notice the drag, and which does eventually abate no matter how right your person is) the misunderstandings and terrible fights*** don’t FEEL good but over time seem to be trending you upward into a kinder, more resourceful, more intelligent communicator who is finding ways of getting closer and closer to your own values—then this relationship is the generative kind of hard. You might still want to take the occasional well-deserved month in your hermitage, and you might benefit by some couples counseling or communication training to lessen the wear-and-tear of your fights, but overall, the pain of your arguments is not evidence that you are with the wrong person.

If, in the friction and drag of your relationship, the misunderstandings and terrible fights*** are making you feel less and less resourceful as a person, or eroding your (or your partner’s) confidence, or you are drifting farther away from your values and don’t like the person you are turning into—this conflict is damaging. Take a really thoughtful look at the way you are showing up in your relationship and the way your partner is showing up, think about what needs to change, and get the support you need to do it. Whether you end the relationship or choose to stay and make supported shifts in the way you interact, something does need to change.

***I’m talking about misunderstandings, here, not physical or psychological violence. If you are experiencing either, please get support—here’s a list of resources to explore. If you are having trouble discerning whether what is happening in your relationship is physical or psychological abuse, please talk to someone—one of the dynamics of abuse is that it messes with our ability to think clearly. Here’s a post on how to find a counselor.

Notice that there is not an option three in which the relationship is not hard.

Conflict in relationship is inevitable. I can say this with relative confidence because I have lived alone in the woods for long stretches of time and had difficulty getting along with myself. Additionally, I have a partner who has been scientifically rated by objective bystanders to be the most understanding human on the planet, and I’ve found ways to quarrel and suffer even so.

If you find that there is no conflict in your relationship, I would hazard to guess that one of four things is happening.

1) You may be collapsing your reality to avoid conflict with your partner, which is not healthy for you.

2) Your partner may be collapsing their reality to avoid conflict with you, which is not healthy for them.

3) You may be in a position where you and your partner are not communicating much or in depth, in which case you are paying for low conflict with low intimacy.

4) You are the enlightened being we are waiting for. Please stop reading this blog and run for office immediately.

So –respectfully—

There is no right person with whom a truly intimate relationship will not be difficult.

But it’s important that relationship is difficult in the right ways.

“Okay,” said my client. “I think I get it. I’ll give you the ‘it depends’ this time but you are running up against your monthly limit of therapyspeak.”

“Fair.”

“But are you saying I should just accept all this constant fighting?”

“Not at all. I’m saying don’t be too quick to decide you’re with the wrong person just because there’s conflict. It’s still entirely possible you’re with the wrong person. But you’re using the wrong criterion.”

“So how do I know if we should stay together?”

“You’re the only one who can make that call. But, if you’re game, bring me two lists next week: things you love about your partner and your relationship, and things that are completely not working. And write up one of your arguments so I can see what it’s like. We’ll go from there.”

“And what’s YOUR homework?”

Which is how this blog post came to be.

Thank you to my client for the willingness to share this story. Details have been changed to protect privacy. (But that thing with the sandtimer absolutely happened. Well played.)

If you like to learn through stories, you might appreciate the depth storytelling events I’m offering this year. The next one is April 30th, 2024, and you can attend online (from anywhere in the world) or in person ( in Western NC). Details below.

Am I Crazy?

By Lissa Carter, LCMHCS

He sat very quiet and still on the couch, as far from me as his body could go. His face was drawn. In a whisper he said “it’s going to sound so crazy what I am about to say. And it might be hard to hear.”

And then he proceeded to say something so human, so relatable, that I could not keep my head from nodding along. When, after a few moments of silence, his eyes rose and clocked me nodding, his face registered shock.

“You understand what I’m talking about?” he asked.

“As a counselor and as a human: yes. Extremely relatable,” I responded. His shock melted slowly into laughter.

Why do we do this to ourselves? Why do we believe that our behavior, our feelings, our thoughts, hold us apart and unwanted from the greater river of humanity? Why do we so unerringly believe that everyone --except for, specifically, us --was given the manual for life?

Most of us have learned, through trial and error, that trying to control others does not end well. We’ve learned, through relational pain, to attune and connect to those we love, even when we don’t understand why they are behaving the way they are.

(And sometimes we forget, and try to control, and remember why it doesn’t work, and start again. Yes, I’m looking at you, Self.)

Yet relatively few of us seem to turn that knowing back on ourselves. Rather than attune inside, rather than treat ourselves with love and curiosity when we are struggling or unsure, we berate, discipline, and control ourselves. And, slowly, that inner relationship deteriorates until we think of ourselves as little more than a set of actions and products.

Over time, if there is no space between who we are –our innate value as a human being—and the outcomes of our actions and products, something even more dire occurs. Because if I AM my actions and products, then any criticism, any feedback at all, about those actions or their products is intolerable. Because it feels like criticism of my selfhood. So I must defend against feedback in any way possible, must resolutely avoid either feedback itself or any truth it may contain. Which, then, in a terrible spiral, begins to deteriorate my relationship with others.

But what if we were to reverse that spiral?

What if my response to the feedback of someone I love is –once I’ve fed it through my psychological boundary to ensure the feedback is accurate and coming from a trustworthy source—to take in the parts that are true and helpful?

This builds the trust between me and the person I love. Now, through the feeling of attunement with this person, I remember my innate goodness. Rather than punishing myself for having “gotten something wrong”, I can feel compassion for the way in which I continue to try, and for the aspects of myself that were perhaps misunderstood in this encounter.

From here, I begin slowly to build a space between who I am and the roles I play, the actions I perform, the results I get. And I can take refuge in that space when others offer me constructive feedback—refuge enough that I can hear the impact my presence has on others, and allow it to inform and grow me, without feeling personally attacked.

Of course it’s never that graceful, continuous, or easy, but there is such a direct connection between the way we treat ourselves and the way we treat others that no matter which side you start with—the way you talk to yourself or the way you take in the feedback of others—transformation will flow in this circle, self to other, other to self.

And this might—eventually—call me crazy—be the way we stop waging war. On ourselves, on other people, species, countries.

After my client and I had processed a little, I asked him if I could share an impression with him. He consented, and I told him “when I hear you say to me that I might think you are crazy, my impression is that’s not about me. My impression is that somewhere inside, you are saying to yourself ‘this is crazy. I’m crazy.” He nodded. “So—if that’s true—what happens next?”

“What do you mean?”

“When you hear yourself saying ‘I’m crazy’—what happens next?”

“I feel sad, I guess. Or I tell myself something to do—go to the gym usually, something a normal sane person would do.”

“So there’s no response?”

“I don’t get it.”

“When you said to me—I might think you are crazy—I responded. I said ‘that’s very relatable actually.’”

“I see what you mean. Yeah, no, there’s no response. Or the response is “okay, crazy, go the gym and act normal!”

“What if we shoehorn in something between the “I’m crazy” and “go to the gym like a sane person.” What if we put in there something like what I said—a response. Something like “it’s frightening to feel crazy—is there anything you need?” or “I bet a lot of people go through this, is there someone you’d like to talk to?” Something that expresses care and connection.”

“I mean I could, but I don’t think it would help.”

“It might not. But I am noticing that when you came in here, you were sitting way over there and your face looked scared. And now your voice is more relaxed and you’re leaning in and coming up with ideas and conversation. And that happened because there was some connection around this thing that was making you feel crazy. I’m just saying that can be available inside when it’s not available from other people.”

“Interesting.”

If I protect myself no matter what the world throws at me, I’m safe but I’m an island. If I go unprotected out into the world, I can be utterly devastated by what I hear from others. Self-attunement is a little bubble of safety within which we can take refuge, that allows us to be both protected and connected at the same time. It’s a little bit of sanity each of us can create within ourselves. To protect the world from our crazy, and to protect ourselves from the crazy of the world.

Deep gratitude to my client who gave me permission to share their story—details have been changed to protect their privacy. And thank you to brilliant behavior analyst Shannon Fee for sharpening my thinking on this topic.

One way I build the skill of self-attunement with my clients is through storytelling.

This works in two ways: one, understanding an emotion or psychological dynamic is far easier when amplified through characters in a story than when dissected minutely in your life. Bigger things = easier to see.

Two, getting a little distance through metaphor always helps clarify what we are working with because we don’t get defensive about metaphors or characters in a story. And hearing that a character in a story that has been handed down for hundreds of years is acting exactly the way that you just did? That’s incredibly normalizing.

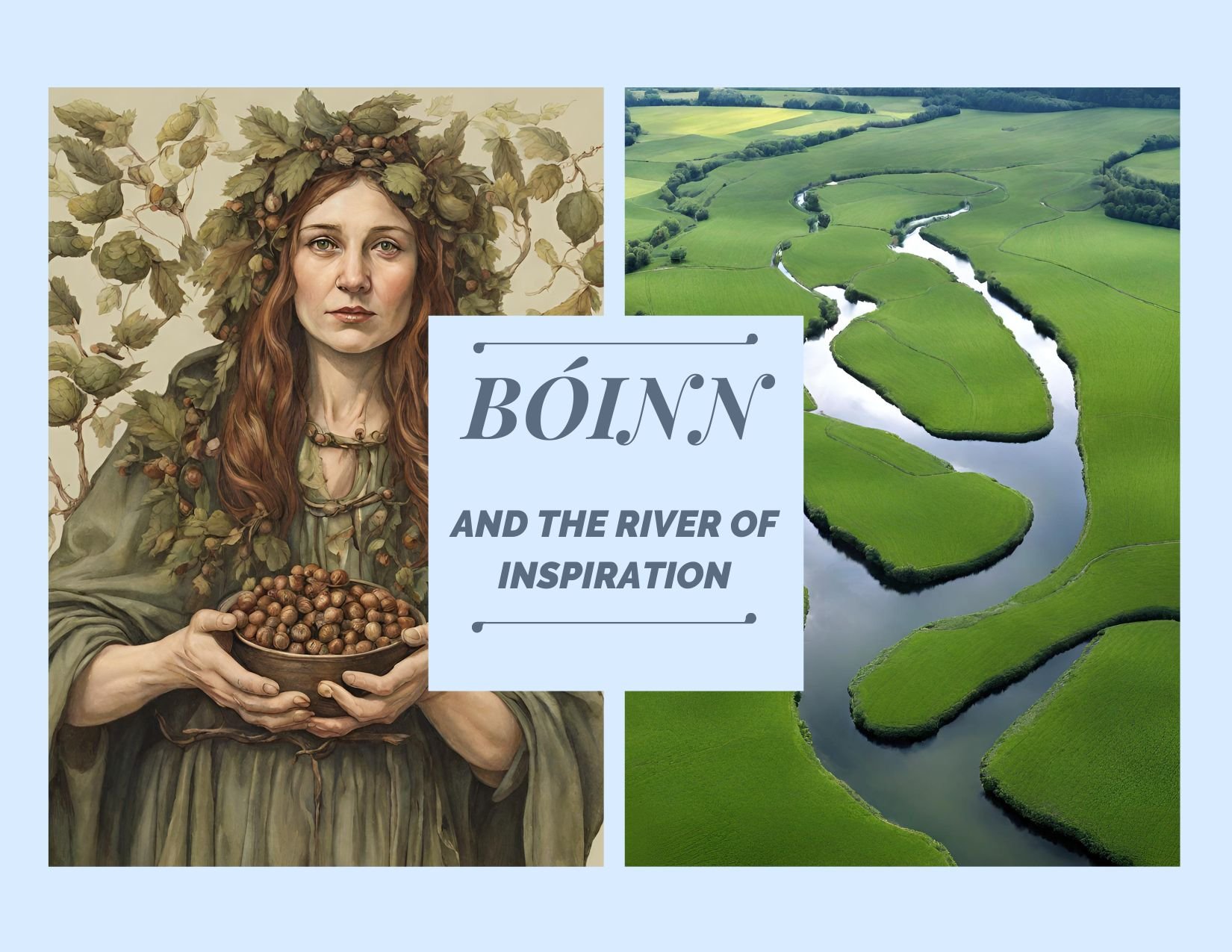

If any of this intrigues you, you might be interested in a storytelling project I’m engaged in this year to give back to the community and to the causes that are close to my heart. The next story I’ll be telling is about boundaries and self-attunement—all the things I’ve been writing about here. It’s called Boinn and the River of Inspiration and you can learn how to join in here.

Dangers of New Years Resolutions

By Lissa Carter, LCMHCS

Whether or not you belong to a tradition that honors the first of January as the beginning of a new cycle, the energy given to personal change this time of year is palpable. The parking lot of the gym I pass on the way to the office has been crammed with cars since the 1st, and conversations with friends and clients revolve around reviewing the year past and naming hopes for the year ahead.

The invitation to reflect on our actions and intentions is welcome. And yet, the pitfalls inherent in the way we approach resolutions can undermine our hopes and plans. Here are three dangers I’ve noticed in New Year’s resolutions, and three filters that help to combat them.

First danger: Setting Goals that are Subtractive

Brains are additive, not subtractive. Let me offer an example: while looking for a stud finder at the hardware store this morning, I located a brand called “StudBuddy” (everyone, this is not a Freudian blog. StudBuddy is a device that locates two-by-fours beneath sheetrock) and for the rest of the morning found myself whistling the jingle for arguably creepy 80’s toy “MyBuddy”.

My brain never erased that jingle –it’s still there, all these years later. I could write new lyrics—“Stud buddy! Stud buddy! When it beeps that’s where the na-ai-ail goes!”—and remember them too—but, given a relatively normal developmental arc, my brain will not erase the original jingle. It’s there for keeps.

Which is some of the reasoning behind why, when setting intentions and objectives, it’s advisable to avoid “Dead Man Goals”, which are anything a dead man could do better than you. For example: be calmer with my children, argue less with my partner, eat less sugar, drink less alcohol. That metaphorical dead man would clean the floor with me on any one of them.

Each one of these goals requires me to subtract something to achieve success. And much to my dismay, even if the reward were free tickets to Ireland to attend a sacred storytelling festival, I would not be able to erase the &%@#!% “MyBuddy” jingle from my brain.

You can avoid this pitfall by setting intentions that are additive, not subtractive. For example: I’d like to start more of my mornings with a walk outside. Or, I’d like to read a chapter of an inspiring book every week.

Second danger: Framing Intentions Around Self-Improvement

Let me hasten to say, there is nothing wrong with noticing behaviors or attitudes that are harmful to you, your relationships, or your communities and working to make more values-congruent choices.

Programs of discipline and improvement do work. They work to change behavior. And they work to change behavior, usually, at the cost of the relationship.

How do you feel about someone who is trying to discipline you? To improve you? Even if you agree with their longterm ideas, the act of being disciplined or targeted for improvement tends to erode that relationship. This can be fine when the relationship is short-term or narrow, and specifically chosen to create improvement, such as with a coach or a supervisor.

But when the relationship is with your very self—the one person you will never be able to retreat from—the cost-benefit ratio of eroding relationship to improve performance becomes incredibly steep. Quality of life tanks when the person closest to you is more concerned with improving you than with relating to you. And when quality of life is low, it is difficult to muster the kind of energy and focus necessary to carry out self-improvement projects anyway!

Instead of self-improvement and self-discipline, I would propose self-attunement.

Self-attunement resembles a loving parent-child relationship. A loving parent isn’t going to allow a child to run into traffic or hit another child. But neither are they going to bully their child, or call them names. A parent who is truly attuned to their child will be both kind and firm, neither accepting inappropriate behaviors nor endangering the relationship to enforce discipline.

In a situation of attunement two things happen: one, strong emotions and incongruent behaviors are immediately de-escalated due to co-regulation with a calm, loving person. And two, the feeling of being understood and accompanied makes the situation that triggered those strong emotions and incongruent behaviors feels more bearable, making a little room to consider other options for response.

Often, counterintuitively, it is the relationships where we feel accepted—as Carl Rogers said—exactly as we are, within which we can achieve lasting change. And regardless of the kind of parenting we actually received as children, every one of us is capable of creating attunement with ourselves. It’s the difference between telling yourself what to do, and checking in with yourself kindly to see what you might need in order to be able to accomplish the things that matter to you.

Third danger: Framing Intentions Around Comparison

We humans have an innate bias, when resources are scarce, to form “in” groups and “out” groups. We exclude and dehumanize those who seem different than ourselves. It’s heartbreaking to witness the immensity of suffering caused by this tendency to dehumanize others. And although it is easy to see it on the scale of war, it’s harder to notice it within our own minds. One subtle way this bias appears is through a lens of comparison.

If I say, for example, that I want to be “as successful as Y” or “as strong as X”, underlying both of these intentions is the subtle belief that Y and X are separate from me. Viewed through this lens, the world is a dangerous, competitive place where the resources I need can be snapped up by others.

But viewed through a more ecologically accurate lens of interdependence, I could notice that Y’s success and X’s strength are resources in a community that nourishes me, as well—and that my support of X and Y would ultimately benefit me, too.

By setting intentions that are collaborative rather than competitive we can begin to build the muscle of seeing the world interdependently. In this way we can shift “I want to be stronger than X” to “I want to build strength so that I can be more active in my community and a resource for my grandchildren.” Caring for the trees around you because you know their health directly contributes to the quality of the air that the people you love are breathing feels different than pressuring yourself to be a better environmentalist this year. And we are more likely to stick with behavioral choices that feel good.

Three filters: Additive, Attuned, and Collaborative

So what if this year, rather than steaming in under full power of our latest self-improvement plans, we were to approach our own hearts gently, with curiosity, and check in on the feelings and hopes living there? What if we could work with the heart, body, and mind, exactly as they are, to move toward the choices that feed the kind of person we want to be?

As you sit with your intentions and hopes for the year to come, ask yourself: Am I trying to subtract things I don’t want, or am I moving toward the things I do want? Am I disciplining myself or am I respectfully attuning to myself? Am I approaching these changes individualistically and comparatively, or am I viewing these changes as interdependent and collaborative?

Working with the filters

Let’s try the process on a common resolution. Let’s say that, originally, your resolution was to drink less alcohol this year.

Putting that through the first filter of additive instead of subtractive goals, you might consider what positive outcome you hope to achieve by drinking less. You notice that you are hoping to be less numbed out and more present. You might end up with a modified resolution that sounds something like to meditate every day this year.

Putting that through the second filter of attunement, you might notice that there will be days you don’t want to meditate or might push yourself to meditate in a way that doesn’t feel present at all. You might end up with a resolution along the lines of to add a pause before I drink, and ask myself what I am feeling, thinking, and needing in that moment.

Taking that and putting it through the final filter of collaboration, you might consider the impact on your relationships and actions when you follow through on your intention. Then your final resolution might sound something like: Before I drink this year, I want to add a pause to check in with myself, and to ask if what I am doing is in service to the kind of person I want to be.

This resolution is more likely to succeed, less likely to undermine your relationship with yourself, and is predictive of greater connection and peace of mind overall. Of course your example might sound completely different, even if you were working with the same original resolution. And that’s important, because whatever you land on needs to speak directly to you: your values, and your relationships.

Wishing all of us a year of peace, right relationship, and ever-increasing consideration of ourselves and of others.

As always, I love to hear from you—feel free to comment below or reach out directly to innerlightasheville@gmail.com.

Rest, Play and Just Being: Essential Practices for Integrating Life's BIG Changes and Challenges!

In life, just like some unmapped walks in the woods, just when you think you’ve found a clearing or at least a clear path, you may find even more tangles of brambles or terrain changes to contend with! At such times, keeping moving may be less productive than taking a break and enjoying the light through the branches.

Rest, Play and Just Being: Essential Practice for Successfully Integrating Life’s BIG Changes and Challenges

By Julie King Murphy, NCC, LCMHCA

What? Not another crisis or change! Though periodically life may seem more or less routine, it’s also full of jarring twists and turns. Multiple major events will happen back-to-back or even simultaneously, and suddenly you are living the adage, “when it rains, it pours!” Life-altering experiences such as a significant injury or illness, financial hardships, the start or end of an important relationship or even a new phase of life will demand that we make adjustments, even if we didn’t feel recovered from the last major change. Sought-after experiences, too, can lead us to reconsider priorities, such as where we live, how we spend our time, who we regularly interact with, and even how we understand ourselves. All of these situations are times for the process I call integration, where one learns to adjust to a new experience, reflecting on the impact of this experience and how or whether other changes may be needed in perspective, beliefs, goals, or way of life to experience a greater sense of wholeness and joy.

Many of life’s challenges are manageable within the framework of our pre-existing supports and coping skills we have developed along the way. However, at other times, we may not feel capable of the tasks that life seems to be demanding or even know what to do next. Perhaps, our previous way of managing life’s challenges just isn’t working in this new situation, or an event may have shaken even our core beliefs or taken away something or someone we utterly relied on? The process of integration requires courage to face our new circumstances, self-awareness, self-compassion, and a focused commitment to take actions that will help us creatively manage a new experience of change, as well as the willingness to seek and accept help from others.

All of these tasks require energy—but the pace of our lives can be exhausting!

When we are exhausted, even small changes are unmanageable. Since life’s changes are so often unpredictable and simultaneous, we can’t save our play and rest time for the more routine periods of our life! Even during periods of intense change, we need to play and to rest as part of our conditioning for the integration process that we are in the midst of and for the next one—for another big change may be arriving today! Stilling ourselves or making time to laugh or get into the flow of something we love doing can be hard when we are going through something particularly painful or if we are habitually pushing ourselves to achieve or a fast pace is our only pace. Tired of trying so hard? If life has been challenging enough lately, perhaps you will use my support as a counselor and a coach through your current process of integration. You can also visit my studio and office as a place to still your soul for a while to practice the critical “nonwork” of being.

Rest, Play and Just Being

Whether you are in the midst of a demanding period of integrating change or you are engaged in life in a more routine way, taking time for rest and for play are essential practices to take care of yourself and experience who you are and life’s goodness! The creative process of life is not all work. Enjoying life means really experiencing it—often what you and those around you will really benefit from most is your relaxed and smiling self or the energy you gain from experiencing that smile or flow! Some moments in life are most productively spent just being yourself. Experience life by being immersed in it in a comfortable “at home” sort of way, and take a break sometimes even from the process of integrating life’s latest big change. Just be.

When we relax into being, we can revel in the wonders of life and restore ourselves for other more action-oriented tasks. Later, we can take that experience of just being who we really are and offer that true self more energetically into all experiences. We can observe in the natural world the lesson that while change is constant, some periods of rest and relative stillness or just swaying in the breeze are a part of the ongoing process of life. As we sense who we are, apart from the work that we do, we can feel in new ways the connection with others and with the natural world around us and in us.

When we practice times of “just being” balanced with other times of courageously taking a closer look at ourselves and our lives when the elements of our life are not seeming to fit together or when we have lost our way, we strengthen our capacity for experiencing wholeness and joy. We can feel more attuned to ourselves and know what brings us joy. We can remain in touch with that sense of wholeness and joy, in a way that I would describe as a wordless yet felt and lasting memory or an awareness of who we are and who we are becoming, even at times of great challenge or suffering. I have found this learning in my own life and in witnessing and hearing about the experiences of others.

It's worth noting that one may fear resting or “just being” because we know we may also feel pain or discomfort more at times when we are less busy. But awareness of our experience of suffering is an important part of understanding how we want to live and what changes we hope to make, as well as gathering the energy and motivation to do the work that may be required. But, again, resting doesn’t mean wallowing in discomfort or even sitting with our pain. As we slow toward a point of rest, we may become aware of pain, but as we practice resting –yes, for some, it may take practice and support to rest, we take a break from working and also we let go of our suffering for a time. Resting may take the form of being creative. Resting may be walking alone or with a friend or pet or laughing at a story or a memory. Resting may also be sitting still, practicing mindfulness. People rest in all sorts of ways! When we rest, play, create and share with others in ways that feel honest or authentic, then we open ourselves to feel wholeness and joy again. We strengthen ourselves for the inevitable work ahead!

I feel so much joy and wholeness when I support others in their processes of integration, creative play, and rest. If you need someone to sit with you while you get your own inner stuff out to take a look at it and decide what you will do with it, or if you want to play for a while in the delight of artmaking or practice meditation or just sitting in a comfy room or taking a walk outside, then contact me. I am happy to sit with you, walk with you, create with you, or provide other witnessing support, as you integrate your life’s new experiences, navigate the way you want your life to go, or practice the essential art of “just being.”

Innerlightasheville.com

We are ready to provide support as you identify your resources to overcome obstacles. We’ll help you recognize how far you have already come and what you are indeed capable of accomplishing! Plus, we are excited for the days ahead when much of what you hope for starts becoming a part of your story.

I’m Julie. I know life is messy and often quite rough! But—your artist child within knows: messy can sometimes even be fun!

.

Defeated by ever larger things

By Lissa Carter, LCMHC

A century ago, poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote: "The purpose of life is to be defeated by greater and greater things."

THANK YOU, RILKE! What a profoundly helpful reframe for the cultural message we so often receive, the message that the purpose of life is to constantly improve, to be ever more productive, to become better and better versions of ourselves, to gain ever more success and develop an ever increasing quantity and quality of skills.

I feel exhausted even writing these words down, and yet I know these messages play their way across my own mind thousands of times per day. And they certainly play across the minds of my clients—-sometimes, therapy even gets enlisted as one of the self-improvement projects on the to-do list!

But if—as Rilke suggests— the meaning in these impermanent, flawed, frustrating lives of ours is not to constantly improve, not to heap success upon success—but, instead, to dare the defeat, to allow the transcendent beauty and awful tragedy of life to utterly overwhelm us—then, perhaps, therapy can be less about self-improvement and more about meaning-making.

“Wait just one ever-loving minute!” I hear you cry, “Isn’t the whole point of therapy to STOP feeling so utterly overwhelmed? To become more functional?”

Certainly, we don’t want to walk around overwhelmed all the time. And yet, if our “answer” to the pain of life is to constrict ourselves, to narrow the comfort zone until our lives are bound by only certain successes, that narrowness does not limit only our defeats. Our sense of joy is diminished, our playfulness, meaning itself is narrowed. We can’t pick and choose what grows smaller when we restrict our lives to include only successes and comfortable feelings. Everything shrinks.

So, as I often tell my clients: the goal here isn’t to feel better. It’s to FEEL better. To allow oneself to expand, to feel more, to dare the realms of human experience that are less comfortable, less sure. Because when we expand the circle to include those realms, the circle widens all the way around and our joy—our sense of meaning and purpose—increases too.

And if we look at the way the brain works to retain information, there’s more data to back up Rilke’s assertion. Try as we might, we can’t subtract information from the brain. There are around two large “pruning” events in the brain that happen in a human lifetime, and we are not in charge of what makes the cut. Other than these events, if we want to modify information our brain holds, we can’t simply subtract the things we no longer believe. We have to add. We have to grow ever larger.

Much as I might wish I could, I can’t subtract the core belief, forged in early childhood, “I am a misfit, I do not belong.” But over the years I can add to this belief: “And there are people who love me.” “And there are places I feel at home.” “And there are contributions that I can make.” Over time, although the primary and painful belief does not go away, the many additions we make modify it so profoundly that it not longer impacts us in the same way.

When we are completely honest with ourselves, much of this “self-improvement” we are engaged in is actually avoidance of some kind. I don’t want to feel judged as unintelligent, so I listen to psychology podcasts instead of music. I hate the feeling of anxiety, so I go for a run to try and escape it. I’m not moving toward the person I want to become—I am running from the feelings I am afraid of. Yet if I try to subtract the belief “I am a misfit, I do not belong” by avoiding the arenas of life that trigger this uncomfortable thought or feeling, life won’t get better. It will just get smaller.

At any given moment we have a choice: to move toward the person we want to be, or to move away from discomfort. When we choose to move away from discomfort, it’s so often because we don’t want to be defeated. We don’t want to risk the pain of rejection or imperfection in the pursuit of our dreams.

But if the goal is not perfection, or even success—if the goal is to be defeated today by something that is incrementally larger than the thing that defeated you yesterday—doesn’t that make it a little bit easier to turn toward the person you long to become?

One final thought on this—often my clients speak of the work they do in therapy as “self-discipline”. The discipline to practice their values, the discipline to choose relationality over fear, the discipline to keep their commitments. When this happens, I like to draw their attention to the etymology of the word discipline—-it shares a root with “disciple”.

What are you a disciple of? What matters enough to you that you put yourself in discipleship to that quality, no matter how uncomfortable it might get?

As for me, I want to be in discipleship to compassion, to generosity, to kindness, to equity. Often these qualities lead me into uncomfortable conversations and thorny dilemmas. And yet—they are beautifully large things to be defeated by.

Thank you to the client who inspired this post by saying “these ideas need to be on the internet!” You know who you are <3

Want to dip a toe into Expressive Arts? Join Julie King Murphy for the Midday Makers series…an opportunity to dedicate your lunch break to creative exploration!

As always, please feel free to comment below or reach out directly to innerlightasheville@gmail.com.